Dale Earnhardt Jr.'s Plane Crashes With Him and His Family on Board!

F or centuries western culture has been permeated past the idea that humans are selfish creatures. That cynical paradigm of humanity has been proclaimed in films and novels, history books and scientific inquiry. Merely in the terminal 20 years, something extraordinary has happened. Scientists from all over the globe have switched to a more hopeful view of flesh. This development is even so and then immature that researchers in different fields often don't even know about each other.

When I started writing a volume virtually this more hopeful view, I knew in that location was ane story I would have to accost. It takes place on a deserted island somewhere in the Pacific. A plane has just gone down. The only survivors are some British schoolboys, who can't believe their adept fortune. Nil just beach, shells and water for miles. And amend notwithstanding: no grownups.

On the very first day, the boys institute a democracy of sorts. One male child, Ralph, is elected to be the group's leader. Able-bodied, charismatic and handsome, his game program is unproblematic: 1) Have fun. 2) Survive. 3) Make smoke signals for passing ships. Number 1 is a success. The others? Non so much. The boys are more interested in feasting and frolicking than in tending the burn. Before long, they have begun painting their faces. Casting off their clothes. And they develop overpowering urges – to pinch, to kick, to bite.

Past the fourth dimension a British naval officeholder comes ashore, the island is a smouldering wasteland. Iii of the children are dead. "I should take thought," the officer says, "that a pack of British boys would accept been able to put upward a better show than that." At this, Ralph bursts into tears. "Ralph wept for the end of innocence," we read, and for "the darkness of man's heart".

This story never happened. An English schoolmaster, William Golding, made up this story in 1951 – his novel Lord of the Flies would sell tens of millions of copies, exist translated into more than 30 languages and hailed equally one of the classics of the 20th century. In hindsight, the secret to the volume'due south success is clear. Golding had a masterful ability to portray the darkest depths of mankind. Of course, he had the zeitgeist of the 1960s on his side, when a new generation was questioning its parents virtually the atrocities of the 2d earth state of war. Had Auschwitz been an anomaly, they wanted to know, or is there a Nazi hiding in each of us?

I first read Lord of the Flies as a teenager. I recall feeling disillusioned after, only not for a 2d did I think to uncertainty Golding'due south view of human nature. That didn't happen until years subsequently when I began delving into the author's life. I learned what an unhappy individual he had been: an alcoholic, prone to depression. "I have ever understood the Nazis," Golding confessed, "because I am of that sort past nature." And information technology was "partly out of that lamentable cocky-cognition" that he wrote Lord of the Flies.

I began to wonder: had anyone always studied what existent children would do if they constitute themselves lonely on a deserted isle? I wrote an article on the subject, in which I compared Lord of the Flies to modern scientific insights and concluded that, in all probability, kids would act very differently. Readers responded sceptically. All my examples concerned kids at home, at school, or at summer military camp. Thus began my quest for a real-life Lord of the Flies. After trawling the web for a while, I came across an obscure blog that told an arresting story: "One twenty-four hours, in 1977, vi boys set out from Tonga on a angling trip ... Defenseless in a huge tempest, the boys were shipwrecked on a deserted island. What do they do, this lilliputian tribe? They made a pact never to quarrel."

The article did non provide any sources. But sometimes all it takes is a stroke of luck. Sifting through a newspaper archive one day, I typed a year incorrectly and there it was. The reference to 1977 turned out to accept been a typo. In the vi October 1966 edition of Australian newspaper The Historic period, a headline jumped out at me: "Sunday showing for Tongan castaways". The story concerned six boys who had been found iii weeks earlier on a rocky islet south of Tonga, an island group in the Pacific Ocean. The boys had been rescued past an Australian sea captain after being marooned on the island of 'Ata for more than a twelvemonth. Co-ordinate to the article, the helm had even got a television station to flick a re-enactment of the boys' adventure.

I was bursting with questions. Were the boys even so alive? And could I discover the television footage? Well-nigh importantly, though, I had a atomic number 82: the captain's name was Peter Warner. When I searched for him, I had another stroke of luck. In a recent outcome of a tiny local paper from Mackay, Commonwealth of australia, I came beyond the headline: "Mates share 50-year bail". Printed alongside was a small photograph of ii men, smiling, ane with his arm slung effectually the other. The article began: "Deep in a banana plantation at Tullera, near Lismore, sit down an unlikely pair of mates ... The elderberry is 83 years old, the son of a wealthy industrialist. The younger, 67, was, literally, a child of nature." Their names? Peter Warner and Mano Totau. And where had they met? On a deserted isle.

My wife Maartje and I rented a machine in Brisbane and some 3 hours later arrived at our destination, a spot in the center of nowhere that stumped Google Maps. Yet there he was, sitting out in front of a low-slung firm off the clay route: the human who rescued six lost boys 50 years ago, Helm Peter Warner.

Peter was the youngest son of Arthur Warner, once i of the richest and most powerful men in Commonwealth of australia. Dorsum in the 1930s, Arthur ruled over a vast empire chosen Electronic Industries, which dominated the country's radio market at the fourth dimension. Peter was groomed to follow in his male parent's footsteps. Instead, at the historic period of 17, he ran away to bounding main in search of adventure and spent the next few years sailing from Hong Kong to Stockholm, Shanghai to St Petersburg. When he finally returned five years afterward, the prodigal son proudly presented his father with a Swedish captain's certificate. Unimpressed, Warner Sr demanded his son learn a useful profession. "What'southward easiest?" Peter asked. "Accountancy," Arthur lied.

Peter went to work for his father's visitor, nevertheless the sea all the same beckoned, and whenever he could he went to Tasmania, where he kept his ain fishing fleet. It was this that brought him to Tonga in the winter of 1966. On the way home he took a little detour and that'due south when he saw it: a minuscule island in the azure bounding main, 'Ata. The island had been inhabited once, until one dark twenty-four hour period in 1863, when a slave ship appeared on the horizon and sailed off with the natives. Since then, 'Ata had been deserted – cursed and forgotten.

Just Peter noticed something odd. Peering through his binoculars, he saw burned patches on the green cliffs. "In the torrid zone it's unusual for fires to starting time spontaneously," he told united states, a half century later. Then he saw a boy. Naked. Hair down to his shoulders. This wild animate being leaped from the cliffside and plunged into the h2o. Suddenly more boys followed, screaming at the height of their lungs. Information technology didn't take long for the first boy to reach the boat. "My proper noun is Stephen," he cried in perfect English. "There are half dozen of us and we reckon we've been here 15 months."

The boys, once aboard, claimed they were students at a boarding schoolhouse in Nuku'alofa, the Tongan uppercase. Sick of schoolhouse meals, they had decided to take a fishing gunkhole out i day, simply to get defenseless in a tempest. Probable story, Peter thought. Using his two-way radio, he called in to Nuku'alofa. "I've got six kids here," he told the operator. "Stand by," came the response. 20 minutes ticked by. (As Peter tells this part of the story, he gets a little misty-eyed.) Finally, a very tearful operator came on the radio, and said: "You found them! These boys accept been given up for dead. Funerals have been held. If it'south them, this is a miracle!"

In the months that followed I tried to reconstruct as precisely every bit possible what had happened on 'Ata. Peter's retention turned out to be excellent. Even at the historic period of 90, everything he recounted was consistent with my foremost other source, Mano, 15 years erstwhile at the time and now pushing seventy, who lived just a few hours' drive from him. The existent Lord of the Flies, Mano told us, began in June 1965. The protagonists were six boys – Sione, Stephen, Kolo, David, Luke and Mano – all pupils at a strict Catholic boarding school in Nuku'alofa. The oldest was xvi, the youngest 13, and they had one chief matter in common: they were bored witless. So they came upward with a plan to escape: to Fiji, some 500 miles abroad, or even all the manner to New Zealand.

There was merely one obstruction. None of them owned a boat, and then they decided to "infringe" one from Mr Taniela Uhila, a fisherman they all disliked. The boys took little time to set up for the voyage. Two sacks of bananas, a few coconuts and a small gas burner were all the supplies they packed. Information technology didn't occur to any of them to bring a map, let alone a compass.

No ane noticed the small craft leaving the harbour that evening. Skies were fair; only a mild breeze ruffled the calm bounding main. But that night the boys made a grave error. They vicious asleep. A few hours later on they awoke to water crashing down over their heads. It was dark. They hoisted the sail, which the wind promptly tore to shreds. Next to suspension was the rudder. "We drifted for eight days," Mano told me. "Without food. Without water." The boys tried communicable fish. They managed to collect some rainwater in hollowed-out coconut shells and shared information technology equally between them, each taking a sip in the morning and another in the evening.

Then, on the eighth twenty-four hour period, they spied a phenomenon on the horizon. A minor island, to exist precise. Not a tropical paradise with waving palm trees and sandy beaches, but a hulking mass of rock, jutting upwards more than a thousand feet out of the ocean. These days, 'Ata is considered uninhabitable. Only "past the time we arrived," Helm Warner wrote in his memoirs, "the boys had set up upwards a modest commune with food garden, hollowed-out tree trunks to store rainwater, a gymnasium with curious weights, a badminton court, craven pens and a permanent fire, all from handiwork, an old pocketknife blade and much determination." While the boys in Lord of the Flies come up to blows over the fire, those in this existent-life version tended their flame so it never went out, for more than a year.

The kids agreed to work in teams of 2, drawing up a strict roster for garden, kitchen and baby-sit duty. Sometimes they quarrelled, but whenever that happened they solved it by imposing a time-out. Their days began and ended with song and prayer. Kolo fashioned a makeshift guitar from a piece of driftwood, half a coconut shell and half dozen steel wires salvaged from their wrecked boat – an musical instrument Peter has kept all these years – and played it to help elevator their spirits. And their spirits needed lifting. All summer long it inappreciably rained, driving the boys frantic with thirst. They tried constructing a raft in order to leave the island, but it barbarous apart in the crashing surf.

Worst of all, Stephen slipped one day, cruel off a cliff and broke his leg. The other boys picked their way downward later him and and so helped him back up to the top. They set his leg using sticks and leaves. "Don't worry," Sione joked. "We'll practice your work, while you lie there like King Taufa'ahau Tupou himself!"

They survived initially on fish, coconuts, tame birds (they drank the claret also every bit eating the meat); seabird eggs were sucked dry. Afterward, when they got to the height of the island, they found an aboriginal volcanic crater, where people had lived a century before. At that place the boys discovered wild taro, bananas and chickens (which had been reproducing for the 100 years since the final Tongans had left).

They were finally rescued on Sunday 11 September 1966. The local dr. afterwards expressed astonishment at their muscled physiques and Stephen's perfectly healed leg. Merely this wasn't the stop of the boys' fiddling adventure, because, when they arrived dorsum in Nuku'alofa police force boarded Peter'due south boat, arrested the boys and threw them in jail. Mr Taniela Uhila, whose sailing boat the boys had "borrowed" 15 months earlier, was still furious, and he'd decided to press charges.

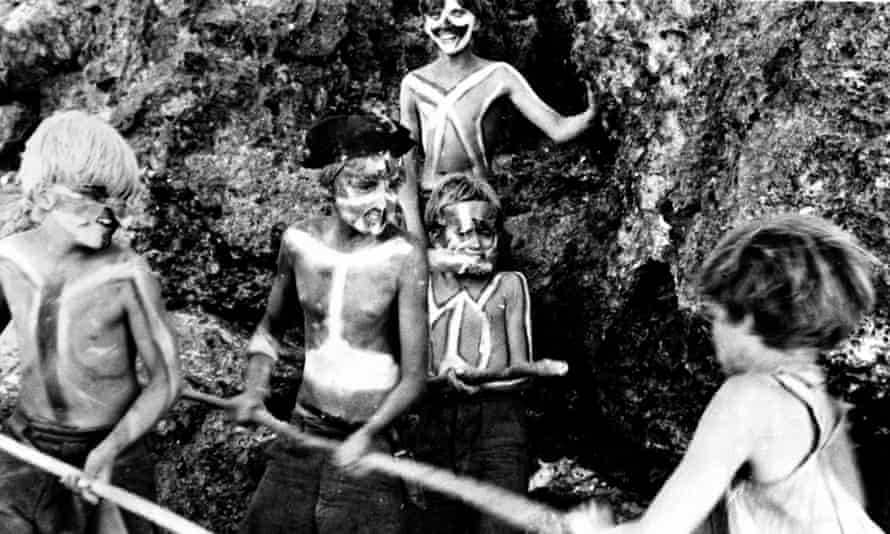

Fortunately for the boys, Peter came up with a plan. It occurred to him that the story of their shipwreck was perfect Hollywood material. And being his begetter'due south corporate accountant, Peter managed the company's film rights and knew people in Tv. So from Tonga, he called up the manager of Aqueduct seven in Sydney. "You can have the Australian rights," he told them. "Give me the earth rights." Next, Peter paid Mr Uhila £150 for his former boat, and got the boys released on condition that they would cooperate with the motion-picture show. A few days later on, a squad from Channel 7 arrived.

The mood when the boys returned to their families in Tonga was jubilant. Nearly the entire isle of Haʻafeva – population 900 – had turned out to welcome them domicile. Peter was proclaimed a national hero. Before long he received a message from King Taufa'ahau Tupou IV himself, inviting the helm for an audience. "Thank yous for rescuing six of my subjects," His Royal Highness said. "At present, is there anything I tin exercise for y'all?" The captain didn't have to think long. "Yes! I would similar to trap lobster in these waters and start a business here." The king consented. Peter returned to Sydney, resigned from his father's company and commissioned a new ship. Then he had the six boys brought over and granted them the thing that had started it all: an opportunity to see the world across Tonga. He hired them as the crew of his new fishing boat.

While the boys of 'Ata have been consigned to obscurity, Golding's book is all the same widely read. Media historians even credit him equally being the unwitting originator of one of the well-nigh pop entertainment genres on television today: reality Television receiver. "I read and reread Lord of the Flies ," divulged the creator of hit series Survivor in an interview.It's time we told a different kind of story. The existent Lord of the Flies is a tale of friendship and loyalty; ane that illustrates how much stronger nosotros are if nosotros tin lean on each other. Later on my wife took Peter'due south picture, he turned to a cabinet and rummaged around for a bit, then drew out a heavy stack of papers that he laid in my hands. His memoirs, he explained, written for his children and grandchildren. I looked downwards at the first page. "Life has taught me a great deal," it began, "including the lesson that you should e'er expect for what is good and positive in people."

This is an adapted excerpt from Rutger Bregman's Humankind, translated by Elizabeth Manton and Erica Moore. A live streamed Q&A with Bregman and Owen Jones takes place at 7pm on 19 May 2020.

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2020/may/09/the-real-lord-of-the-flies-what-happened-when-six-boys-were-shipwrecked-for-15-months

0 Response to "Dale Earnhardt Jr.'s Plane Crashes With Him and His Family on Board!"

Post a Comment